Q & A with Sean Barton, Editor

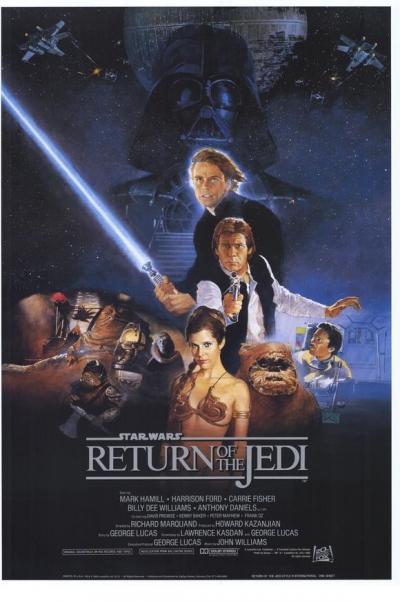

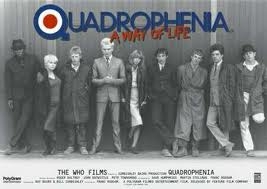

Sean Barton, editor of Quadrophenia, Return of the Jedi and Mutant Chronicles speaks exclusivley to thecallsheet.co.uk about his incredible career

Tell us what you have been working on recently?

I have recently cut Wicker Tree, a strange, enjoyable film by the makers of the original Wicker Man, shot on the Red camera, 4k digital film. I then cut Tracker, an excellent film set in New Zealand in 1903, starring Ray Winstone and Temuera Morrison (Once were Warriors). A classic western really, three men searching for redemption, set in this beautiful landscape. I was over there for 9 weeks. We shot on film, super35mm. It had quite a lot of VFX, greenscreen shots and rig removals. Before these I cut a big visual effects film called Mutant Chronicles, every shot was a visual effect. I haven’t done one for a long time so I wanted to do it to keep my hand in as the technology has changed enormously. It was shot on a Viper, a digital HD system and was a really interesting project. In the last few years I’ve also been re-cutting other peoples films, about 5 I think. I’ve been cutting a natural history feature called Song of the Turtles, a sort March of the Penguins project, I’ve never worked on one of those before and it was very difficult. I’ve tried, in the last few years, not to do the first thing that comes along and to do things I think I’ll enjoy. I try to vary it and look for new projects, The Mutant Chronicles was a big High Def number and a major effects movie, I hadn’t done one of those for a while and it was very different from something like Return of the Jedi, which was all using photographic technology.

Back to your earlier career, what were you like at school and how did you get into the industry ?

I was a dropout, it was the 60’s and I left school at 16 with no qualifications. I worked as a waiter, worked on building sites, drove a truck and even worked in an antique shop. I was looking for something to do that was fun and through friends of mine, I got into being a film electrician. The thing about being an electrician is that you work when nobody else is, and when you have finished your bit of working you stop and wait while they are shooting. I thought that this isn’t work, this is fun! I looked around for a job in film and got a job as a runner at an editing firm called John Farrow Films where they cut commercials. I went became an assistant editor and ended up editing. I got lucky and moved to a company called Natural Breaks, which had Ridley Scott as one of it’s directors, quite a hot company to get in to. Pam Powers was the senior editor and it really took off. I cut commercials, for various companies, for 7 or 8 years and by the end of that I’d of run out of steam, I’d enjoyed it but it wasn’t why I got into the film industry. So I set up my own post production company with two other editors called ‘Cutting Edge’ and we were editing commercials, short films, music videos, documentaries and corporate films. I’d known Richard Loncraine for some years and I recut a film of his called Full Circle, with Mia Farrow and it was great fun. A friend of mine, Dave Humphries, was one of the writers on Quadrophenia and he introduced me to Franc Roddam, I’ve never looked back since.

Did you realise what sort of impact Quadrophenia would have as the rushes came in?

I just knew it was great fun, it was part of my own past and I got along with Franc very well and liked the way he made films. From that, I met Richard Marquand, who I ended up doing six films with. It was a very nice part of my life where I had two or three directors who I would work with regularly, and it’s very satisfying not having to start a new relationship on every film.

Is forming a new relationship with a director a hard part of your job?

It can be. I’ve been teaching at the National Film School and I tell students that it’s the directors film, not yours. You can try and persuade but it’s their film. Also, you have to be able to get on with them and make the relationship work, you spend so much time together, just the two of you that it’s miserable if you don’t get along well.

Is there a big difference between directors that you began working with at Cutting Edge and those you work with now?

Now I seem to work with an lot of directors who are making their first film, it seemed easier because the directors back then had one eye on the next project. The Financing of film has changed a lot, there was much more money spent by the American majors on smaller to medium budget films in England, around $10m and they don’t really do that now. If they are using an American director, they tend to bring the editor and the dop over with them.

Do you like working with new directors now, is that part of the challenge?

New directors are often in there 30’s and some don’t really want their film to be cut by someone who’s old enough to be their father, which I can understand. Most new directors though can see the value of an older editor, with a lot of experience. It varies from person to person

You had worked with Richard Marquand on several projects before ROTJ, how was the dynamic with him and working with George Lucas?

I had worked with Richard Marquand on a film called Birth of the Beatles, which was great fun and then another called The Eye of the Needle, with Donald Sutherland. We showed George Lucas a print of that and it seemed to clinch the deal. Richard was signed up to direct Return of the Jedi. Richard said to me, “I’d love you to cut it, but I’m not going to not do it, if you don’t get it!”. So I paid for myself to travel out the states and met with George. He liked Eye of the Needle and Quadrophenia and it was a very successful relationship, we worked very closely together for over a year over in Marin County. I did some of the second unit directing as well. The way of working was very good, there was enough money in every department and they weren’t saving pennies everywhere.

When did you learn about getting the job of editing Return of the Jedi and how did you feel about the honour of handling the third part of a beloved trilogy?

You just sorted of dive in and tackle it all head on, you never had time to worry. The whole machine was very impressive. ILM (industrial light and magic) was next door and we could walk through all of the stages of the visual effects, which was fascinating. George was a very easy, gentle person to work with and quite shy, it was quite a jolly, pleasant atmosphere. I don’t think we were under the gun for the most part, but towards the end of it all, he did say ‘people might be tired of this by now’. He was wrong but I could see what he meant.

You are in high demand for stories that involve SFX – There are around 2000 fx shots in the Mutant Chronicles. How does one set about editing with shots that don’t even exist yet and how is has the technology evolved?

The nice thing about cutting digitally, either on Avid or Final Cut Pro, which is better for editing effects on, is that I can show the digital fx team exactly what I want. When I was working on Jedi, there was just blue screen. When for example a Luke falls into the pit at Jabba’s Palace, the monster didn’t exist at all, except for a giant hand that picked Luke up. I had shots of Luke, reacting to a Blue screen, I had to make up the timings, once everyone agreed my cut I didn’t see it again until they had put the creature in. It was really winging it and you have to have faith. Now I can be reasonably precise, you can even write on the screen so that everybody knows what you want. The director of Mutant Chronicles was technically very good and shot plates of background and foreground so I could do rough comps all the way through. He said one of the reasons he choose me for the film was because some editors weren’t comfortable with using Final Cut Pro and shooting on digital Hi Def, but those were the things that attracted me to it. There were a few weeks of banging my head against the wall when I started cutting on Final Cut Pro but I got there and know I can cut on both FCPro and Avid.

What part of the process for you is the most thrilling?

The first cut is very exciting because you don’t really know what you’ve got til you cut it. I find it hard work, because of all the decision making that’s involved in getting there. I love seeing the layers added as well, the music, visual effects, and all those components being added is immensely enjoyable to watch.

Do you feel isolated as an editor and how do you work to combat that?

In post production, it’s not terribly useful to work long hours. I find that if I work for 12 hours one day, I’ll have to come in the next day and re-cut my work because my levels of concentration drop and your work isn’t as good. It’s important to get out and have a social life with family and friends because it effects the quality of your work if you become too isolated. I remember working on a live action ‘Pinocchio’ in Prague and we worked 15 weeks, 6 days a week and 12 hours a day, often more. The quality of work had completely gone because everybody was ready to drop, everyone was walking in slow motion and the work wasn’t any good. In the US, New Zealand and Australia, they work 5 day weeks. That gives the director a rest day, and a day to think about the week ahead. Otherwise, all you do on your rest day is sleep. In Australia, they say it’s dangerous to work 6 day weeks because of the risk of serious accidents.

What would you like to see more or less of in the British Film industry?

Everything seems to go on cycles of what’s popular. We are in the middle of a horror cycle at the moment and before that, we had the romantic comedies after four weddings and gangster movies after Lock, Stock. I’d like to see more diversity, the French film industry makes very diverse pictures at the same time. Because we are trapped in the same language as the Americans, we tend to make bad imitations of US movies, which I don’t think really work. I’d like to see more indigenous films being made here. The types of films that sell overseas are those such as Four weddings or The Full Monty, they have an English peculiarity to the humour and the sensibility. I think it does well on the international market because people are fascinated by that. Lots of people like French movies because of what they tell you about that culture. As an example, I was up for but didn’t get ‘Control’ about Ian Curtis. It was a brilliant script, I met the director and really wanted to do it. They had terrible problems with the money, it kept dropping out, going away and they had to delay. In the meantime, I was offered horror movie scripts that were clunky and predictable but had already got the finance in place. In the end, Control was made for less than the original budget. There was lots of indecision and short sightedness from the backers, not being able to see the album that you could tie into the film for example. I’d also like to see a proper union. Bectu has become rather toothless and doesn’t have real interest in freelancers but the Unions in the US really work for freelancers. They can work out different rates for different budgets, it’s very organised and gives proper protection.

Finally, If you could have edited any film, what would it have been?

There’s so many. Almost any Peter Weir Film as they are so cleverly constructed. Witness was a great film I would have loved to have edited. Adaptation is another, I loved that and wish I could have been a part of it. Most of the off beat films, Michael Clayton was a really lovely film, I love the way it was cut.

Sean Barton is represented by McKinney Macartney.

thecallsheet.co.uk is a members only network for professionals working in Film and TV in the UK. With over 2,000 members and a database of over 40,000 productions, people and companies, we make it easy to find the best in the industry.

This article was originally published in 2011.