The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance

The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance on Netflix.

Interview with Gaffer Andy Lowe

Andy Lowe is a Gaffer working in Film and TV in the UK. His breakthrough feature working as a Gaffer was on Shane Meadows’s ‘This is England’ and subsequently went on to Gaffer Four Lions, Annihilation, Suffragette, The Crown and Paddington 1 & 2.

Having just worked with DoP Erik Wilson on Paddington 2, Andy joined Erik to work on the spectacular new 10-part Netflix production of The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance, a prequel to the 1982 Jim Henson classic.

The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance is released today on Netflix. It’s a prequel to the 1982 Film. How did you and Erik Wilson (DoP) approach the look and feel of the series?

I think the first thing we did was watch the original, just to understand what the world of Dark Crystal is. It always feels important to create a world on any project I think, to know where the boundaries of the world are, to figure out what’s important. And that felt especially relevant on this project. There are lots of limitations on a project like this (working with puppets; all sets built on rostrums; no natural light as we’re only shooting in a studio) but embracing these limitations creatively and understanding how they shape your decision making is important. Just knowing we were facing the same limitations as they would have faced in 1982 felt reassuring as it felt we were creating the same world from the off.

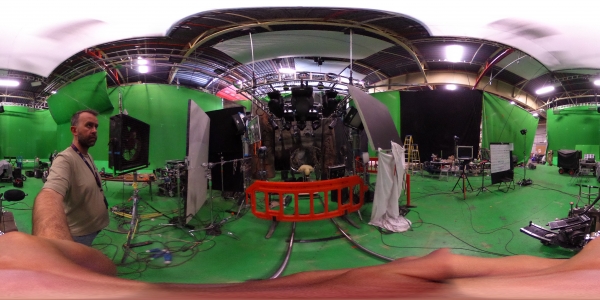

Where did you shoot The Dark Crystal and can you tell us about the scale of the sets and the characters?

We shot in 2 warehouses in West London. They were pretty big spaces (200’x200’ and 25’ high). They weren’t sound-stages as that wasn’t important as all the sounds would be recorded later.

All the sets were built on rostrums, 4’ high. The rostrums and floors were all removable in sections to give the puppeteers space to work.

And the scale of the characters I guess is 1:1, although because they’re all fantasy characters I’m not sure that’s how best to classify them. Nothing is miniature is what I’m trying to say. A Gelfing is about 3’ tall, a Skeksis 6’ or 7’ tall, Land Striders maybe 10’ tall, but with a huge variety of characters in-between! It was really something to see the puppeteers bring them to life.

You shot on sound stages for over 10 months. Did you have a permanent lighting rig set up and what were the key lights that you used throughout this production?

Although we were on sound stages for 10 months, very few of the sets stayed built for the whole of that time. In fact, I don’t think any set was up for the duration. Building and striking of the sets was happening constantly, which meant we were always rigging and de-rigging lights too. If we were shooting on A Stage for a week, sets and lighting would be happening on B Stage. Then the next week we’d swap. Nothing was permanently installed really, except for some cables and distribution boxes.

We tried to use a variety of lights, just to keep things changing. Within the world of Dark Crystal there are 4 or 5 different ‘lands’, so for one land we’d use some HMI, for another older tungsten lamps. We had a lot of LED lamps, which we’d bounce into windbags above the sets. SkyPanels and SpaceForces were our go-to lamps for that. That’s how we created our exterior daylight feel. Then we’d add shafts of hard light from our HMI or Tungsten lamps.

One really useful thing was because there was no dialogue to record we could use moving lights too. A lot of time it’s not possible to use these on a film set because they have fans and motors that make noise, but on this it was great. These type of lights meant we could create a new look or adjust a look really quickly.

We also used a lot of battery-powered LED lights too, particularly 1x1 Fomex’s, Ice Lights and Astera AX1s. These were great sources for us when we needed to get a light in last minute, especially when the rostrums had been removed so we couldn’t set a light on a stand or run cables. One of the electricians could jump in with the puppeteers and get the light exactly where it was needed.

We also had a brilliant practical lighting department, lead by Dom Aronin, who made bespoke lights for props and art department. Some of the solutions they came up with were fantastic. Lots of tiny, dimmable, colour changing LEDs. The whole world of Dark Crystal was created from scratch. No prop or piece of the set was bought ‘off-the-shelf’, and that applied to in-vision lights too. Lots of research and planning and time and labour went into these lights too.

When you were in pre-production with Erik and Gavin Bocquet (Production Designer), how do you arrive at those decisions on kit selection for lighting?

One thing that helped was that I had almost as much prep as Erik. I think I had 10 weeks of prep, which sounds like a lot but is also never enough. It felt good to be involved early, just to get my head around what Gavin and the Art Department were well into planning.

During that time, we tested as much as we could. Erik already had an idea of what gel colours he wanted to try. And we tried as best we could to match those colours to the RGB moving lights and LED lights we’d started to think about using, so we had a palette of colours to work with.

And I attended the PLASA lighting trade show while I was in prep. I was very fortunate that the show was on at that time. I try to go to the BSC Show whenever I can make it as it’s really useful to see what new technology is coming into our industry. But PLASA is more theatre and concert based, which was much more appropriate to the style of Dark Crystal.

When you’ve got creatures of very different shapes and sizes on set, and you’ve got green suited puppeteers, what unexpected challenges does that present you with compared to a normal shoot?

I guess the main thing was that there was quite often no floor. The puppeteers need to work in a ‘pit’, so that’s challenging as you can’t put lights on stands or run cables. So as much as possible lights need to be rigged from the ceiling, which in itself was a huge logistical challenge. Rigging Gaffer John Antill and HOD Rigger Steve Fitzpatrick did amazing work getting our lights in the right positions. It was never easy for them but they always managed it.

But a lot of our work on the shooting days was following the puppeteers lead really. In a lot of ways, you end up ‘puppeteering’ lights too, moving with the puppeteers, reacting to what they’re doing. We’d be moving lights during a take, which you’d do very rarely on a ‘normal’ job. So it was great to be able to do that. This could be electricians jumping in with battery lights at the last minute, or Desk Op Nathan Porter making changes on the fly, again during takes, or even adding more practical lights or interactive lights at the last minute too. Anything that added to the richness of the world felt like the right thing to be doing, and we took inspiration from the puppeteers to do that.

With the volume of productions shooting in the UK at the moment, have you found that some kit is unavailable to hire? If so, what’s the most sought-after gear?

To be honest, I thought it would be a problem, but I’ve not found it to be the case. There are 3-4 big lighting companies in the country at the moment, but they’ve all invested pretty heavily in kit. It helps if you can have alternatives in mind though. And I’ve learnt it’s really important to know all the lights. So if you’re told that SkyPanels aren’t available you need to know what’s an appropriate substitute.

It seems to me that the new LED kit lights are the most sought after lights. All the lighting companies have SkyPanels and other LED panel light sources, but lots of the kit lights they seem reluctant to buy. I think this is because there are new lights coming out every month, each job I do there seems to be a new LED light in fashion. And there are some great lights out there now. But I understand the lighting companies not wanting to buy them, as they’re a big investment quite often, and in a month or 2 people might be asking for a new ‘latest’ light. It’s tricky, but I think that’s because we’re in a real revolution in terms of new lights on the market.

In the Dark Crystal, you’re lighting for physical creatures often on a green screen, but on Paddington, you’re often filming on a character that either isn’t on set or a double/green/mo-cap. How do you approach those two different setups?

There wasn’t that much more green screen work on Dark Crystal than on lots of other types of job. They were puppets in physical space most of the time, so you could just light them like you had actual actors in front of the camera. That’s not to say there’s not a ton of VFX work to do (and quite often a lot of our lights to paint out of shot .. or paint into shot depending on your point of view) but this didn’t affect our lighting.

And to be honest, Paddington isn’t that much different either. That was a big realisation for me, that just because Paddington wasn’t there, on set, you still had to light as if he was. The set still needs to be lit the same way, the real actors still need to be lit well, and the VFX department need to record references of the lighting as it was planned by the DoP. Treating the set like the character is really there keeps your decision making simple. You just have to understand how your decisions impact other departments, and in a way that applies to puppeteers and VFX in very similar ways.

Has pre-vis changed the way you light a scene?

I think it has as it helps understand what the director and DoP or VFX Supervisor are thinking, which when you’re dealing with fantasy or imaginary characters is invaluable. It's the old cliche of a picture (or previz!) painting a thousand words. You can understand their intentions quickly which again means your decision making is quicker and simpler.

Film technology has changed rapidly in the last 20 years, what do you think has been the biggest change in the lighting department?

To me, it felt like the lighting department was a little slow to the digital revolution. If digital cameras have been around for 20 years, it feels like only in the last 5 years new LED technology has been catching up. I think that’s why things are changing so quickly now. LED has passed its infancy now, but it’s still got a lot of growing to do. That's very exciting to be part of.

And I think the biggest change that hasn’t happened yet is to do with how we provide power to film sets. That we’re still mainly using diesel generators feels like an old technology that it’d be good to see a shift away from. There are some signs that this is happening, especially in battery and mobile power technology, but it’s not something that’s quite caught on yet.

You’ve also shot several short films as a DoP. What did you learn about gaffering from being the DoP on those projects?

I think the main thing is understanding the relationship between lighting and the camera. I think you need to have an understanding of each department’s priorities, but understanding how cameras and lenses and LUTS and grip equipment all work together is incredibly important as a gaffer, so you know as best as you can that how decisions you’ll be making about lighting affect what’s happening inside the camera.

How did you start your career and what was the best piece of advice you’ve been given?

I started working on MA graduate films in Sheffield and then moved onto working on low budget features.

I think 2 bits of advice served me well. The first was that there isn’t anything in the film industry that can’t be explained in 10 minutes, there’s no big secret to it how it all works, it’s just hundreds of little things to try and understand. And the second was advice from producer Barry Ryan, who went on to set up Warp Films, who said when I was working on low budget shoots in Sheffield, often for free, that I should try and get a new piece of kit on each job, something I hadn’t used before, even if it wasn’t something the job needed, just so I could use it, play with it, break it even and then fix it, but just get used to how it worked. Even if it was something simple like a Magic Arm or a Kinoflo light, just get your hands on it. This was an amazing bit of advice.

Tell us about how you choose your team and what qualities you look for in new entrants to the lighting department.

I think with a team it’s really important to have people with a variety of skills, even within the one department. The group of electricians that my Best Boy, Chris Stones, has put together is tight and we’ve all worked together for years now. We know each other’s strengths and weaknesses. It doesn’t seem that useful to have a group that can only solve problems the same way. Having a few different approaches seems useful to me.

And I think with new entrants to the lighting department, and even with experienced crew members to do with new technology, it’s good to be interested and inquisitive, to know when to listen and when to ask questions, to be keen and not be afraid to say when you don’t understand what’s being asked of you. Things happen very fast on a film set and there are always last-minute ideas that need implementing in a hurry, and I know I can be guilty of blurting instructions out too quickly at times, but there’s nothing more frustrating than someone not understanding what’s been asked of them and going off doing the wrong work. I’d always rather be asked to clarify what I mean than someone doing 10 or 30 minutes work that was a waste of time.

What is the shot or sequence you are most proud of?

I think in Dark Crystal, it’s probably the scene where Rian escapes from the Throne Room by climbing up the falling chandeliers. There were over 600 individually created and wired bulbs in those chandeliers, all flickering through the lighting desk, and all falling on separate cues. It was really exciting when that worked as it was months of work for everyone involved.

If you could change one thing about the film industry, what would you choose?

I wish the lighting department was more inclusive and diverse. It’s a lot of white men and I’m not exactly sure why that is. The industry as a whole has problems with inclusivity, but lighting and rigging seem to be the worst culprits as departments go.

If you ever get any time off, how do you relax?

Hopefully with a holiday!

The Dark Crystal is now streaming on Netflix.

Andy Lowe is a member of thecallsheet.co.uk.